Tokyo, 23 April, /AJMEDIA

Inside Egypt’s Great Pyramid of Giza lies a mysterious cavity, its void unseen by any living human, its surface untouched by modern hands. But luckily, scientists are no longer limited by human senses.

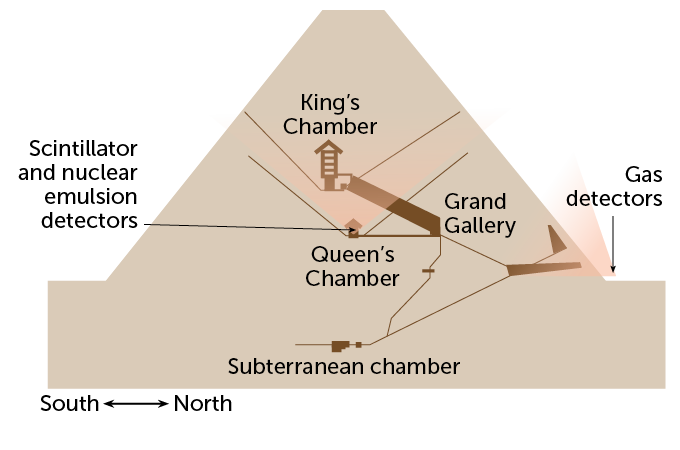

To feel out the contours of the pyramid’s unexplored interior, scientists followed the paths of tiny subatomic particles called muons. Those particles, born high in Earth’s atmosphere, hurtled toward the surface and burrowed through the pyramid. Some of the particles imprinted hints of what they encountered on sensitive detectors in and around the pyramid. The particles’ paths revealed the surprising presence of the hidden chamber, announced in 2017 (SN: 11/25/17, p. 6).

That stunning discovery sparked plans among physicists to use muons to explore other archaeological structures. And some researchers are using the technique, called muography, to map out volcanoes’ plumbing. “You can see inside the volcano, really,” says geophysicist Giovanni Leone of Universidad de Atacama in Copiapó, Chile. That internal view could give scientists more information about how and when a volcano is likely to erupt.

Muons are everywhere on Earth’s surface. They’re produced when high-energy particles from space, known as cosmic rays, crash into Earth’s atmosphere. Muons continuously shower down through the atmosphere at various angles. When they reach Earth’s surface, the particles tickle the insides of large structures like pyramids. They penetrate smaller stuff too: Your thumbnail is pierced by a muon about once a minute. Measuring how many of the particles are absorbed as they pass through a structure can reveal the density of an object, and expose any hidden gaps within.

The technique is reminiscent of taking an enormous X-ray image, says Mariaelena D’Errico, a particle physicist at the National Institute for Nuclear Physics in Naples, Italy, who studies Mount Vesuvius with muons. But “instead of X-rays, we use … a natural source of particles,” the Earth’s very own, never-ending supply of muons.

Physicists have typically studied cosmic rays to better understand the universe from whence they came. But muography turns this tradition on its head, using these cosmic particles to learn more about previously unknowable parts of our world. For the most part, says particle physicist Hiroyuki Tanaka of the University of Tokyo, “particles arriving from the universe have not been applied to our regular lives.” Tanaka and others are trying to change that.

Awkward cousins of electrons, muons may seem like an unnecessary oddity of physics. When the particle’s identity was first revealed, physicists wondered why the strange particle existed at all. While electrons play a crucial role in atoms, the heavier muons serve no such purpose.

But muons turn out to be ideal for making images of the interiors of large objects. A muon’s mass is about 207 times as large as an electron’s. That extra bulk means muons can traverse hundreds of meters of rock or more. The difference between an electron and a muon passing through matter is like the difference between a bullet and a cannonball, says particle physicist Cristina Cârloganu. A wall may stop a bullet, while a cannonball passes through.

Muons are plentiful, so there’s no need to create artificial beams of radiation, as required for taking X-ray images of broken bones in the doctor’s office, for example. Muons “are for free,” says Cârloganu, of CNRS and the National Institute of Nuclear and Particle Physics in Aubière, France.

Probing pyramids

Muography proved itself in a pyramid. One of the first uses of the technique was in the 1960s, when physicist Luis Alvarez and colleagues looked for hidden chambers in Khafre’s pyramid in Giza, a slightly smaller neighbor of the Great Pyramid. Detectors found no hint of unexpected rooms, but proved that the technique worked.

Still, the idea took time to take off, because muon detectors of the era tended to be bulky and worked best in well-controlled laboratory conditions. To spot the muons, Alvarez’s team used detectors called spark chambers. Spark chambers are filled with gas and metal plates under high voltage, so that charged particles passing through create trails of sparks.

Now, thanks to advances in particle physics technologies, spark chambers have largely been replaced. “We can make very compact, very sturdy detectors,” says nuclear physicist Edmundo Garcia-Solis of Chicago State University. Those detectors can be designed to work outside a carefully controlled lab.

One type of resilient detector is built with plastic containing a chemical called scintillator, which releases light when a muon or other charged particle passes through (SN Online: 8/5/21). The light is then captured and measured by electronics. Later this year, physicists will use these detectors to take another look at Khafre’s pyramid, Kouzes and colleagues reported February 23 in the Journal for Advanced Instrumentation in Science. Compact enough to fit within two large carrying cases, the detector “can be carried into the pyramid and then operated with a laptop and that’s all,” Kouzes says.