Tokyo, 22 March, /AJMEDIA

Bailenson, who founded Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab, then paused the recording and walked through the class. His avatar gliding, he explained how these playbacks will produce insights into what social life will mean in the “metaverse.” Of course, he doesn’t know what he’ll discover, just like the many companies that are now busily touting this much hyped but as-yet-unformed next evolution of the internet.

Bailenson doesn’t like the word metaverse. He prefers virtual reality. But irrespective of what it’s called, he acknowledges it’s here.

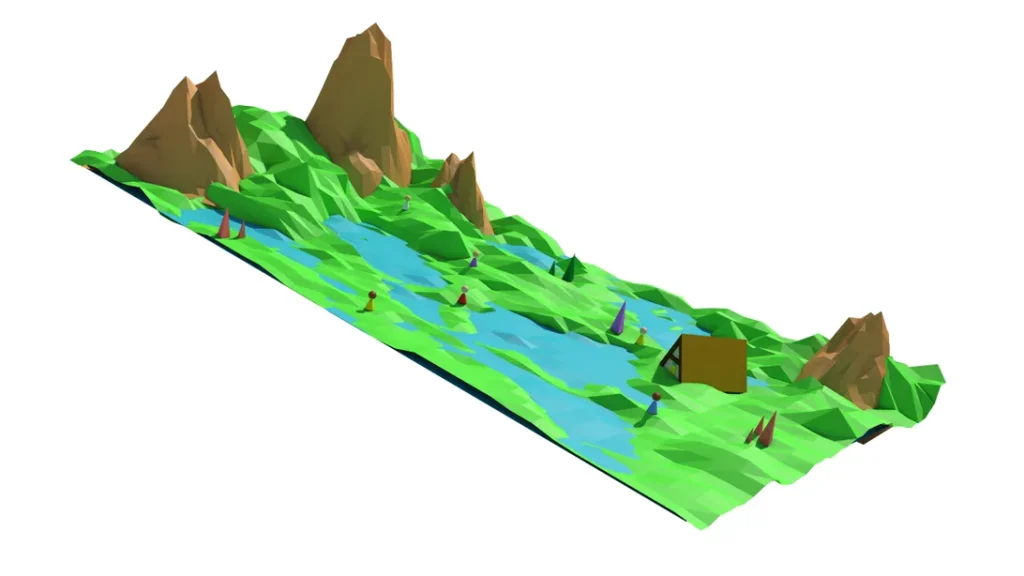

“We’re at a moment in time where the things that I’ve been personally talking about for 23 years since I started in VR in 1999, we can do it now,” he told me after I put on an Oculus Quest 2 headset and joined his class via Engage, an app for creating virtual worlds.

The term metaverse has drifted around the internet for years. First, a fictional concept — sci-fi author Neal Stephenson coined the term in his 1992 novel Snow Crash — it mirrored behaviors in online communities that already existed. It’s reemerged over time. Virtual worlds have been around for decades: Second Life in the early 2000s, now Minecraft, Roblox, Fortnite and newcomers like Decentraland and a host of others. It’s a topic of discussion at trendsetting conferences, like the recently held SXSW festival and the Game Developers Conference, which starts Monday.

The definition of the metaverse is in constant flux. Many refer to it as a shared, persistent digital space for meetings, games and socializing. Avatars, often cartoon-like 3D figures, gather in virtual rooms, have meetings and leave. Others see the metaverse as a layer on top of the existing internet, a set of expanding protocols enabling interconnection between apps and platforms. It’s unclear if there’ll be a single metaverse (“the metaverse”), multiple metaverses (“a metaverse”) or a combination of both. Maybe it’s best thought of as a metaphor for the internet’s continual change.

The concept was rebooted when Mark Zuckerberg rechristened Facebook as Meta last October, a move that pinned Facebook’s future to widespread adoption of the metaverse. He’s been trying to get people interested in VR for years, spending $2 billion for headset maker Oculus in 2014. Meta doesn’t share specific sales numbers, but since the Quest 2 headset launched a year and a half ago, it’s estimated to have sold about 10 million units, one of Zuckerberg’s milestones for larger-scale adoption.

Rebranding, of course, doesn’t ensure success. But it’s undeniably great marketing. Searches for the term “metaverse” barely registered on Google Trends before Zuck’s October pitch, but soared to peak popularity shortly after.

I’ve been exploring virtual spaces for years. In 1996, I wrote a play about chat rooms and virtual worlds, called Utopia Parkway, in which a doctor spent his time online creating virtual replicas of his family. I wrote another in 1998 about MMORPGs, or massively multiplayer online role-playing games.

I’ve covered VR and its close relative AR, or augmented reality, for a decade at CNET. I’ve followed as the term metaverse was stretched to peddle crypto and NFTs, market games and promote entertainment. I’ve watched the hype cycle around the metaverse wax and wane. Now it’s waxing again.

A host of new technologies are converging: VR, AR, high-speed networks, blockchain technologies and wearables. All these technologies get cited when companies discuss the metaverse. Still, I paused when CNET’s copy chief asked me for a definition of the metaverse. I wasn’t sure if there was one metaverse or many. I wasn’t sure if it was simply a new way to refer to virtual worlds, which have been around for years. It seemed like old roads being repaved.

Metaverse: A term in transformation

David Chalmers, a philosopher at New York University, has been thinking about the nature of virtual existence since the original Matrix movie. Back in 2003, Chalmers wrote a philosophical essay about The Matrix as part of the movie’s official website. It’s led to his deeper work on simulations and virtual worlds decades later.

In his new book, Reality+, Chalmers argues that virtual worlds can be as real as our everyday reality, a conclusion he’s reached while spending the pandemic hopping in and out of them to meet with friends.

Chalmers sees the meaning of the term metaverse having shifted since he started writing his book. “The metaverse is no longer a single virtual world or even a cluster of virtual worlds. It’s the entire system of virtual and augmented worlds,” Chalmers tells me over Zoom. “Where the old metaverse was like a platform on the internet, the new metaverse is more like the internet as a whole, just the immersive internet.”

Creating the metaverse — Chalmers sees just one — requires connecting these virtual worlds in a meaningful way. “Community is really important for building meaningful social worlds, actually building communities where people feel invested, like we’re building something here,” says Chalmers, who doesn’t see these types of meaningful connections yet in recent open-world social metaverse apps like Decentraland or Horizon Worlds.

Behind those connections, of course, are big companies. And that concerns Chalmers. Since Zuck rebranded Facebook, many people have begun to see the metaverse as an extension of the social network, Chalmers says, an association that comes with a history of troubling privacy and societal baggage.

“But,” he says, “it’s not that easy to see exactly what the alternative is right now.”