Tokyo, 1 February, /AJMEDIA/

A 57-year-old Maryland man has now survived just over three weeks with the transplanted heart of a genetically engineered pig. His doctor has hailed the operation as a “breakthrough surgery” that could help solve the organ shortage crisis. But from a scientific standpoint, it’s too early in the game to know how much it moves the ball.

The use of animal organs for humans is an idea with a long, dramatic and often disappointing history (SN: 11/4/95). There’s an old saying about xenotransplantation, as the field is known, says Joe Leventhal, a surgeon who heads the kidney transplant program at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. “It’s just around the corner. The problem is, it’s a very, very, very long corner.”

But a rash of new experiments, including three involving pig kidneys transplanted into people being kept temporarily alive on ventilators, has provided tantalizing evidence that achieving the decades-old ambition may finally be in reach.

The recent human operations come after an extensive effort to develop genetically altered pigs with organs that might avoid abrupt rejection, along with further refining of drugs that suppress the immune system and boost survival. That said, the Maryland heart operation was a Hail Mary rescue attempt and not part of a clinical trial — the kind of carefully designed study that is ultimately needed to show whether pig organs can function in humans, and do so safely.

One case can provide some valuable information about how the body responds to the organ, says Karen Maschke, a bioethics scholar at the Hastings Center in Garrison, N.Y., who is editor of Ethics & Human Research. “You may find stuff that you didn’t expect to find,” she says.

But a single snapshot of data doesn’t have enough context to draw conclusions, especially when it involves a gravely ill patient and brand-new technology. Without a study comparing several carefully selected patients, it’s hard to know whether one individual’s experience is typical.

Yet the latest flurry of pig-to-human transplant experiments could help open the door to the kinds of clinical trials that researchers want. That’s the only way to significantly advance the science, says heart surgeon David Cooper of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who has long researched the idea of xenotransplantation. “We’ll learn much more if we are doing clinical cases than if we are staying in the laboratory.”

High on the hog

If clinical trials ultimately prove successful, animals could help ease a critical shortage of donor organs. Of the more than 106,000 Americans waiting for a transplant, around 90,000 need a kidney. Many will die before one is available.

Doctors have previously turned to animal organs in bold, headline-grabbing endeavors. Famed Houston heart surgeon Denton Cooley transplanted a sheep heart as a desperate move to save a dying man in the 1960s; the man’s body quickly rejected the organ.

One of the most high-profile tries at xenotransplantation occurred in 1984 when doctors at Loma Linda University Medical Center in California sewed a baboon heart into a 2-week-old baby born with a fatal cardiac defect (SN: 11/3/84). Baby Fae, as she was known, lived for 21 days and her surgery left a wake of controversy. Some medical ethicists called the operation a “beastly business” that lacked moral clarity. Scientists “beat a hasty retreat back to the laboratory,” according to a 1995 report in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

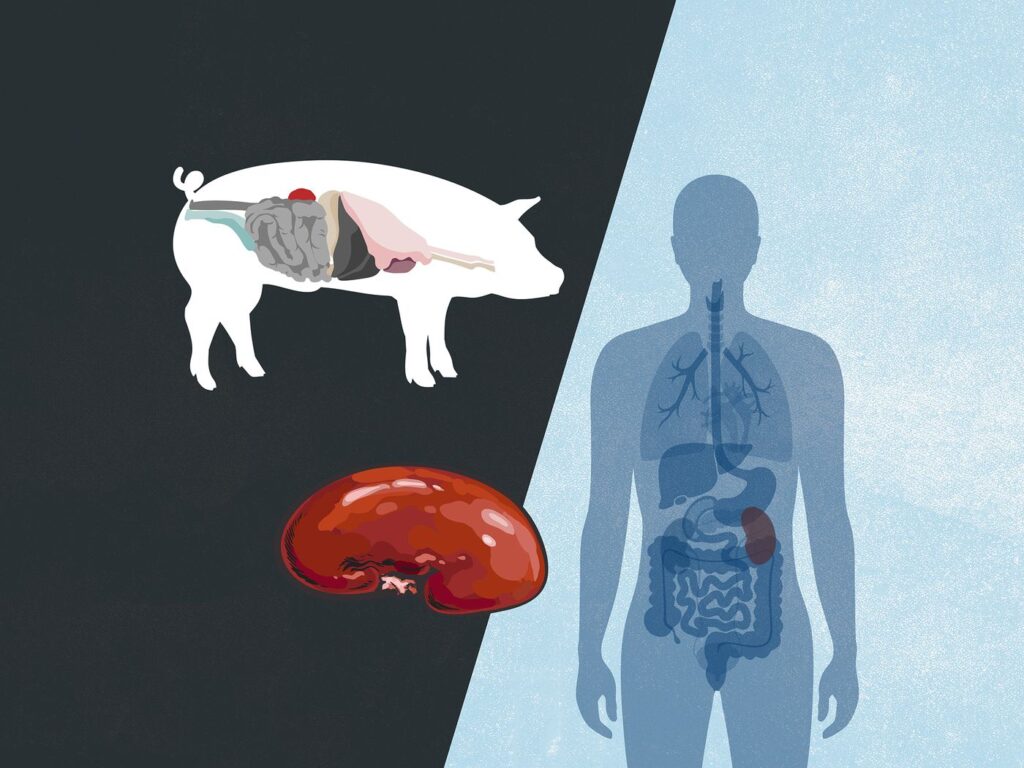

More recently, scientists have focused on pigs, largely because porcine organs are about the size of adult humans’, and the animals are already raised on an industrial scale. Still, the feasibility of the idea was thrown into doubt with the discovery in the 1980s that pig cells are coated with a type of sugar molecule, called alpha-gal, that strongly triggers the human immune system.

The field also experienced a setback with the discovery in the 1990s that the swine genome contains embedded viruses, snippets of viral genetic code woven into pigs’ genetic instruction books. (It’s not just a pig trait; these kinds of viral genes make up an estimated 8 percent of the human genome too.) The viruses, called porcine endogenous retroviruses, don’t bother pigs but might cause problems after suddenly finding themselves in another species.

In the early 2000s, researchers reported the creation of genetically modified pigs lacking alpha-gal, making them theoretically more compatible with the human immune system than a hog straight from the farm. That announcement set off attempts to raise alpha-gal-free animals, most notably in the United States by Revivicor, a company owned by United Therapeutics, based in Blacksburg, Va. Then, in 2020, the possibility of pig-to-human transplants took a giant leap forward, when, for the first time, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Revivicor pigs for human use.

Xenotransplantation also got a boon from CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology and its remarkable ability to snip genes at will. Using CRISPR, scientists can trim the unwanted viral genes from pigs (SN: 8/10/17). “Gene editing with CRISPR has just really helped accelerate the field in sort of a warp drive,” Leventhal says.

In recent experiments, pig kidneys and hearts have been successfully transplanted into baboons. Though the baboons died within days in early xenotransplantation attempts, researchers reported in 2018 that transplanted pig hearts kept beating in the chests of two baboons for about six months, a record at the time (SN: 12/5/18). Other similar experiments have replicated that survival time.

Then, in October 2021, scientists from NYU Langone Health in New York City made the jump to humans: In a test, they grafted a Revivicor kidney onto a person who was clinically brain-dead and watched the organ function for 54 hours, presumably long enough to detect any signs of immediate rejection (SN: 10/22/21). Less than two months later, the same surgical team repeated the experiment. A third such transplant from researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, this time into the abdomen of a man kept temporarily alive by a ventilator following a motorcycle accident, was described January 20 in the American Journal of Transplantation.

None of the kidneys transplanted in people appeared to provoke immediate immune rejection, and the organs even began to produce urine, doctors reported. Given the overwhelming need for kidneys, and proof-of-concept renal tests already done, most experts predicted that the first modern patient to get a xenotransplant would need a kidney.

Then came the unexpected news of David Bennett.