Tokyo, 19 July, /AJMEDIA/

When discussing who is the best Japanese film director of all time, most will say Akira Kurosawa.

The work of directors of his caliber just seems to stay with you for life, as if his art somehow modified your DNA. Certainly, Kanji Watanabe singing “Gondola No Uta” in Kurosawa’s film Ikiru is permanently burned into my soul. This kind of impact that a film has is the hallmark of a great director. Other notable Japanese directors include Hayao Miyazaki, Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu.

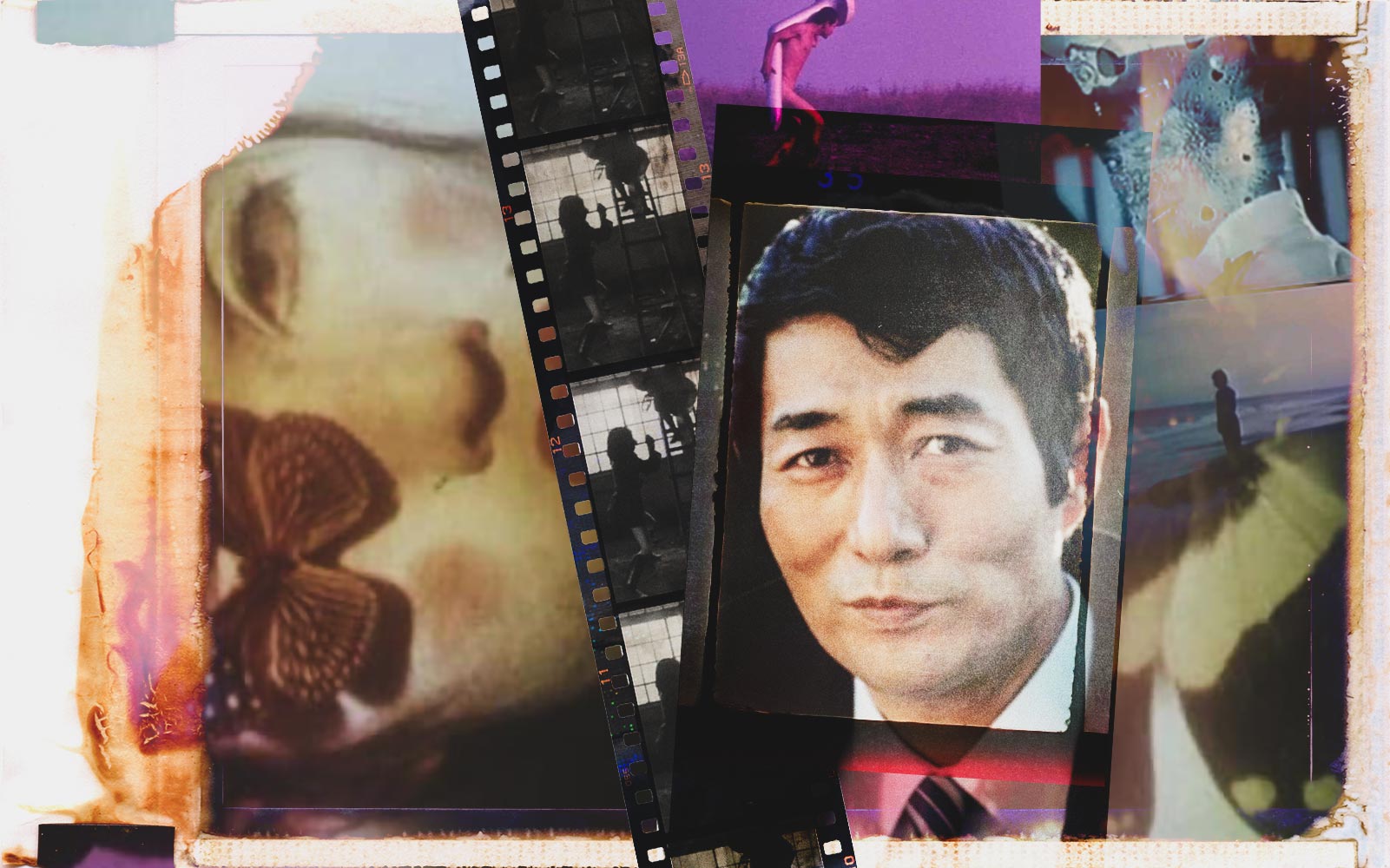

But what about Shuji Terayama? Since 2024 marks the 50th anniversary of his film Pastoral: To Die in the Country (田園に死す) and directors are still putting on the play version of it, his relevance seems like it hasn’t waned at all.

A visceral experience beyond the psychedelic

Watching a Terayama film is like listening to The Microphones’ album Mount Eerie for the first time. When one of his films reaches its climax, it’s a highly visceral experience that can leave viewers with a sense of awe.

His films are full of sexuality, surreal images and fragmented narratives that are disorienting. However, Terayama is not just indulging in decadent psychedelia. Rather, he takes the viewer on very strange journeys in an attempt to communicate powerful messages.

For example, when it’s revealed where the son and his mother are at the end of Pastoral: To Die in the Country, the scene takes on considerable evocative meaning. It’s as if Terayama has been tipping you left and right on a tightrope between reality and his dream world throughout the film. Finally, the rope snaps back and you’re suddenly in a place that is neither here, nor there.

When you finally settle, it feels like you’ve learned something about the human condition in a way that is beyond typical understanding.

Mise-en-scène mastery

Mise-en-scène is one of film’s most difficult concepts to define. In short, this refers to a director’s ability to use not only actors but also props, setting, lighting, etc. to convey meaning as a whole in a scene. Terayama is a master of this. In Grass Labyrinth (草迷宮), when the group of mysterious characters freezes around the female sumo wrestler as she takes her pose, it is easy to see Terayama’s theatrical influence and mastery of the technique.

Striking visuals

Terayama was an innovator of striking visuals.

For example, the double exposure of writing all over the bed sheet overlaid with the sex scene in Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets (書を捨てよ町へ出よう) is ethereal. Or the words written all over the protagonist’s face and body in Grass Labyrinth have a similar visual impact. Yet another striking visual is when Terayama breaks the fourth wall by having the parasol-toting woman wave at the audience directly through the camera in Pastoral: To Die in the Country.

Untangling Terayama’s web

While it is true that Terayama’s feature-length films can be hard to watch, your mind will often come back to the scenes to try to untangle the complex webs he spins. Sion Sono’s film Love Exposure (愛のむきだし) has a similar effect, where watching can be painfully slow, but once over the initial shock, your mind wanders back to the film.

Terayama’s films explore various topics such as sexuality, violence and Japan’s descent into materialism. His exploration leads to universal truths being revealed, but at times these truths confront the viewer with uncomfortable realities that most people suppress. He tackles complex concepts so it is not surprising that his narratives are complex as well.

One thread that seems to be woven throughout most of Terayama’s work is a focus on time and people’s helpless juxtaposition on its continuum. It’s constantly referenced, and wall clocks are prominent props throughout his films. This universal truth is an aspect of Terayama’s work that makes it, ironically, timeless.