Tokyo, 3 May, /AJMEDIA/

Scientists are discovering a surprising bright side for some people with asthma: They are less susceptible to COVID-19.

The very same immune system proteins that trigger excess mucus production and closing of airways in people with allergic asthma may erect a shield around vulnerable airway cells, researchers report in the April 19 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The finding helps explain why people with allergic asthma seem to be less susceptible to COVID-19 than those with related lung ailments, and could eventually lead to new treatments for the coronavirus.

Asthma is a breathing disorder characterized by airway inflammation. The result is coughing, wheezing and shortness of breath. About 8 percent of people in the United States have asthma, with about 60 percent of them having allergic asthma. Allergic asthma symptoms are triggered by allergens such as pollen or pet dander. Other types of asthma can be set off by exercise, weather or breathing in irritants such as strong perfumes, cleaning fumes or air pollution.

Usually, asthma is bad news when it comes to colds and flu. At the start of the pandemic, most experts predicted that coronavirus infections and asthma would be a dangerous mix, says Luke Bonser, a cell biologist at the University of California, San Francisco who was not involved in the study. And that is true for people whose asthma is not triggered by allergies and those with related lung disorders like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD. Those conditions put people at high risk for severe COVID-19.

But as the pandemic progressed, researchers noticed that people with allergic asthma weren’t developing severe COVID-19 as often as expected. Here’s a look at why that may be.

Protein protection

What sets allergic asthma apart from other types of asthma and COPD is a protein called interleukin-13, or IL-13.

Usually, IL-13 helps the body fight off parasites such as worms. Certain T cells pump out the protein, and the body responds by churning out sticky mucus and constricting airways. This traps the worms, holding them in place until other immune system cells can come in for the kill.

“In the case of [allergic] asthma, the body is making a mistake. It’s mistaking a harmless substance, like pollen, for a worm,” says Burton Dickey, a pulmonologist at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston who was not involved in the study.

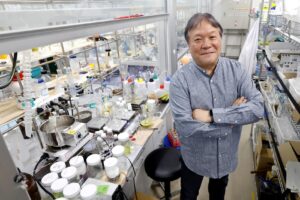

But it wasn’t clear how IL-13 was protecting people with allergic asthma from SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. To find out, pathophysiologist Camille Ehre of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill and colleagues grew cells from the lining of the airways from six lung donors. Some of the cells were treated with IL-13 to mimic allergic asthma. Then the researchers infected some of the cells with SARS-CoV-2.

Lawn trouble

Next on the list of to-dos was to compare how cells that haven’t been treated with IL-13 behave when healthy and when infected with the coronavirus.

Uninfected cells grew in lawns resembling lush grasslands, where the tufts of waving fronds are actually hairlike protrusions called cilia, which grow from the tops of airway-lining cells, the team confirmed. Cilia’s motions help move mucus, and anything stuck in the mucus, out of the lungs.

Cells infected with the coronavirus looked much different. The lush lawn was now slathered in mucus, and bald spots appeared as infected cells died. The doomed cells get squeezed out of the lawn of cilia and inflate like a balloon. The inflation happens partly because chambers called vacuoles inside the infected cells get clogged with viruses. “It’s just filled with viruses, and then it gets kicked out of the club and it blows up and releases all these viruses,” Dickey says.

But not all the cells in the infected lawn were affected equally. Looking at the cells from the side, researchers could see that cells sporting cilia were infected with the coronavirus. But mucus-producing cells called goblet cells, which don’t have cilia, were rarely infected. That may be because a protein called ACE2 decorates the surface of ciliated cells far more often than it does goblet cells. ACE2 is the protein that the coronavirus uses as a door into cells.