Tokyo, 13 February, /AJMEDIA/

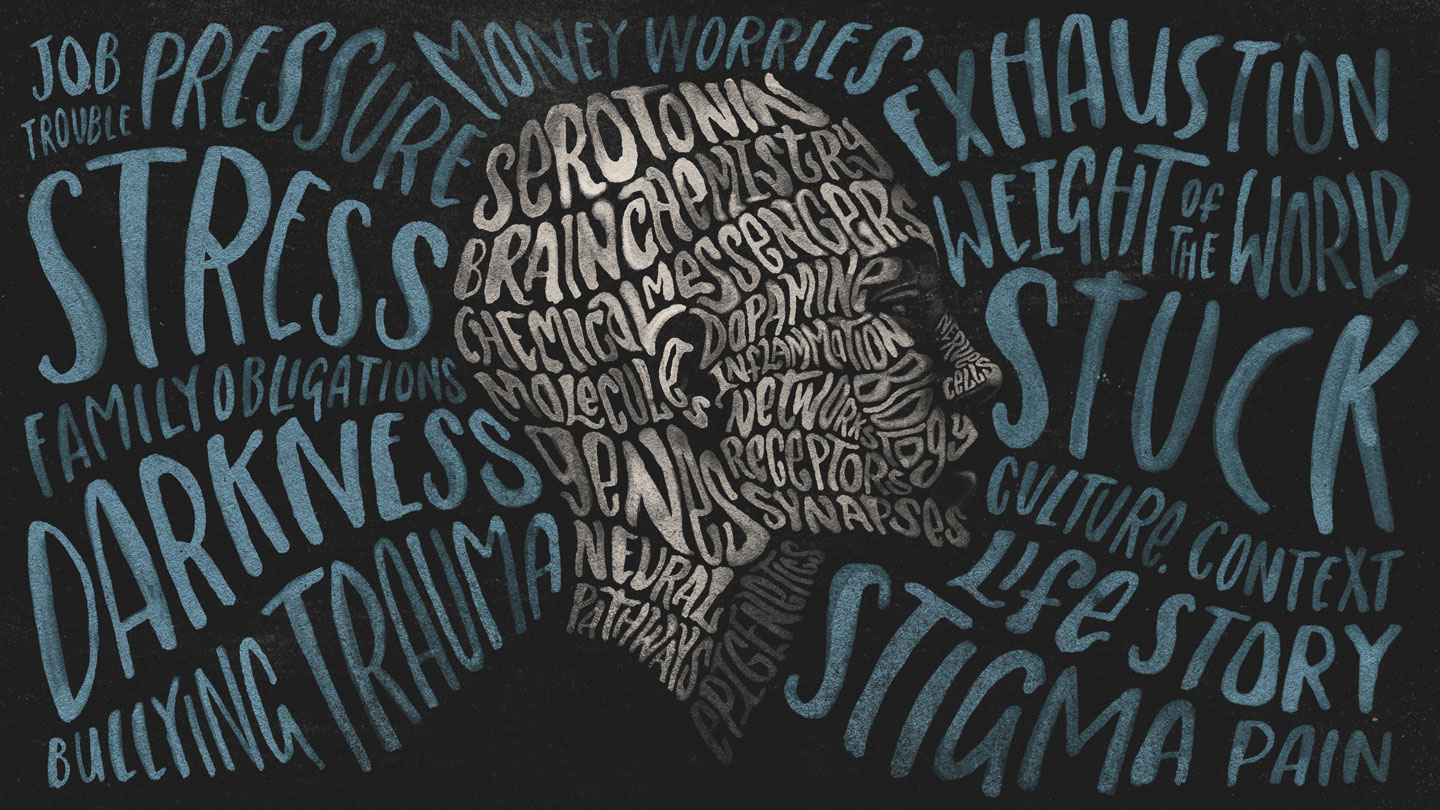

You’d be forgiven for thinking that depression has a simple explanation.

The same mantra — that the mood disorder comes from a chemical imbalance in the brain — is repeated in doctors’ offices, medical textbooks and pharmaceutical advertisements. Those ads tell us that depression can be eased by tweaking the chemicals that are off-kilter in the brain. The only problem — and it’s a big one — is that this explanation isn’t true.

The phrase “chemical imbalance” is too vague to be true or false; it doesn’t mean much of anything when it comes to the brain and all its complexity. Serotonin, the chemical messenger often tied to depression, is not the one key thing that explains depression. The same goes for other brain chemicals.

The hard truth is that despite decades of sophisticated research, we still don’t understand what depression is. There are no clear descriptions of it, and no obvious signs of it in the brain or blood.

The reasons we’re in this position are as complex as the disease itself. Commonly used measures of depression, created decades ago, neglect some important symptoms and overemphasize others, particularly among certain groups of people. Even if depression could be measured perfectly, the disorder exists amid myriad levels of complexity, from biological confluences of minuscule molecules in the brain all the way out to the influences of the world at large. Countless combinations of genetics, personality, history and life circumstances may all conspire to create the disorder in any one person. No wonder the science is stuck.

It’s easy to see why a simple “chemical imbalance” explanation holds appeal, even if it’s false, says Awais Aftab, a psychiatrist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. What causes depression is nuanced, he says — “not something that can easily be captured in a slogan or buzzword.”

So here, up front, is your fair warning: There will be no satisfying wrap-up at the end of this story. You will not come away with a scientific explanation for depression, because one does not exist. But there is a way forward for depression researchers, Aftab says. It requires grappling with nuances, complexity and imperfect data.

Those hard examinations are under way. “There’s been some really interesting and exciting scientific and philosophical work,” Aftab says. That forward motion, however slow, gives him hope and may ultimately benefit the millions of people around the world weighed down by depression.

How is depression measured?

Many people who feel depressed go into a doctor’s office and get assessed with a checklist. “Yes” to trouble sleeping, “yes” to weight loss and “yes” to a depressed mood would all yield points that get tallied into a cumulative score. A high enough score may get someone a diagnosis. The process seems straightforward. But it’s not. “Even basic issues regarding measurement of depression are actually still quite open for debate,” Aftab says.

That’s why there are dozens of methods to assess depression, including the standard description set by the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5. This manual is meant to standardize categories of illness.

Variety in measurement is a real problem for the field and points to the lack of understanding of the disease itself, says Eiko Fried, a clinical psychologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Current ways of measuring depression “leave you with a really impoverished, tiny look,” Fried says.

Scales can miss important symptoms, leaving people out. “Mental pain,” for instance, was described by patients with depression and their caregivers as an important feature of the illness, researchers reported in 2020 in Lancet Psychiatry. Yet the term doesn’t show up on standard depression measurements.

One reason for the trouble is that the experience of depression is, by its nature, deeply personal, says clinical psychologist Ioana Alina Cristea of the University of Pavia in Italy. Individual patient complaints are often the best tool for diagnosing the disorder, she says. “We can never let these elements of subjectivity go.”

In the middle of the 20th century, depression was diagnosed through subjective conversation and psychoanalysis, and considered by some to be an illness of the soul. In 1960, psychiatrist Max Hamilton attempted to course-correct toward objectivity. Working at the University of Leeds in England, he published a depression scale. Today, that scale, known by its acronyms HAM-D or HRSD, is one of the most widely used depression screening tools, often used in studies measuring depression and evaluating the promise of possible treatments.