Tokyo, 12 August, /AJMEDIA/

As Tanina Agosto went through her normal morning routine in July 2007, she realized something was wrong. The 29-year-old couldn’t control her left side, even her face. “Literally the top of my head to the bottom of my foot on the left side of my body could not feel anything.”

The next day, Agosto spoke with a doctor at the New York City hospital where she works as a medical secretary. He told her that she probably had a pinched nerve and to see a chiropractor.

But chiropractic care didn’t help. Months later, Agosto needed a cane to get around, and moving her left leg and arm required lots of concentration. She couldn’t work. Numbness and tingling made cooking and cleaning difficult. It felt a bit like looping a rubber band tightly around a finger until it loses sensation, Agosto says. Once the rubber band comes off, the finger tingles for a bit. But for her, the tingling wouldn’t stop.

Finally, she recalls, one chiropractor told her, “I’m not too big of a person to say there’s something very wrong with you, and I don’t know what it is. You need to see a neurologist.” In November 2008, tests confirmed that Agosto had multiple sclerosis. Her immune system was attacking her brain and spinal cord.

Agosto knew nothing about MS except that a friend of her mother’s had it. “At the time, I was like, there’s no way I’ve got this old lady’s condition,” she says. “To be hit with that and know that there’s no cure — that was just devastating.”

Why people develop the autoimmune disorder has been a long-standing question. Studies have pointed to certain gene variations and environmental factors. For decades, a common virus called Epstein-Barr virus has also been high on the list of culprits.

Now recent studies paint a clearer picture that Epstein-Barr virus instigates MS when the central nervous system gets caught in the cross hairs of an immune response to the virus’s attack. This recognition opens new options for treatment, or even vaccines. Perhaps therapies that target Epstein-Barr itself — or remove the cells in the body where the virus camps out — could jettison the virus before damage is done.

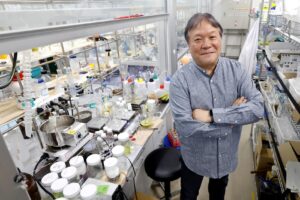

Vaccines might one day “make multiple sclerosis become a historical disease like polio,” says Lawrence Steinman, a neurologist at Stanford University. “The trials will be arduous,” Steinman says. Still, “I think we might be able to put MS in the rearview mirror.”

For now, there’s a lot to learn, including how exactly the virus triggers MS, says Francesca Aloisi, a neuroscientist at the Italian National Institute of Health in Rome.

For many people with MS, even with current therapies, the disease can progress. Right now, Agosto’s symptoms are largely under control. Thanks to physical therapy, an anti-inflammatory diet and medication, she has about 90 percent function on the left side of her body. “Things like long-distance running are out of the question,” she says. Carrying grocery bags with her left arm is a challenge.

Studying the virus’s role in MS “will be an amazing game changer,” says Agosto, who is a patient advocate with the National Multiple Sclerosis Society’s New York City chapter. If Epstein-Barr virus is driving her disease, she wants to know: “How do we get this virus out of the driver’s seat?”

A familiar virus

Multiple sclerosis is an uncommon disease, affecting nearly 3 million people globally. Yet Epstein-Barr virus is almost everywhere.

The virus, discovered in 1964, infects an estimated 90 percent of people around the world. People infected as young children might have a mild cold or show no symptoms. Teenagers or young adults may experience a bout of debilitating fatigue called infectious mononucleosis, or mono, that can last weeks or months.

These symptoms eventually fade. But Epstein-Barr infections hang on. The virus belongs to the herpesvirus family — a group known for instigating lifelong infections. The herpesviruses behind cold sores, genital herpes and chicken pox also stick around for life, usually staying quiet for long stretches. For example, varicella-zoster virus, which causes chicken pox, goes latent inside nerve cells but can resurface to cause the painful disease shingles (SN: 3/2/19, p. 22).

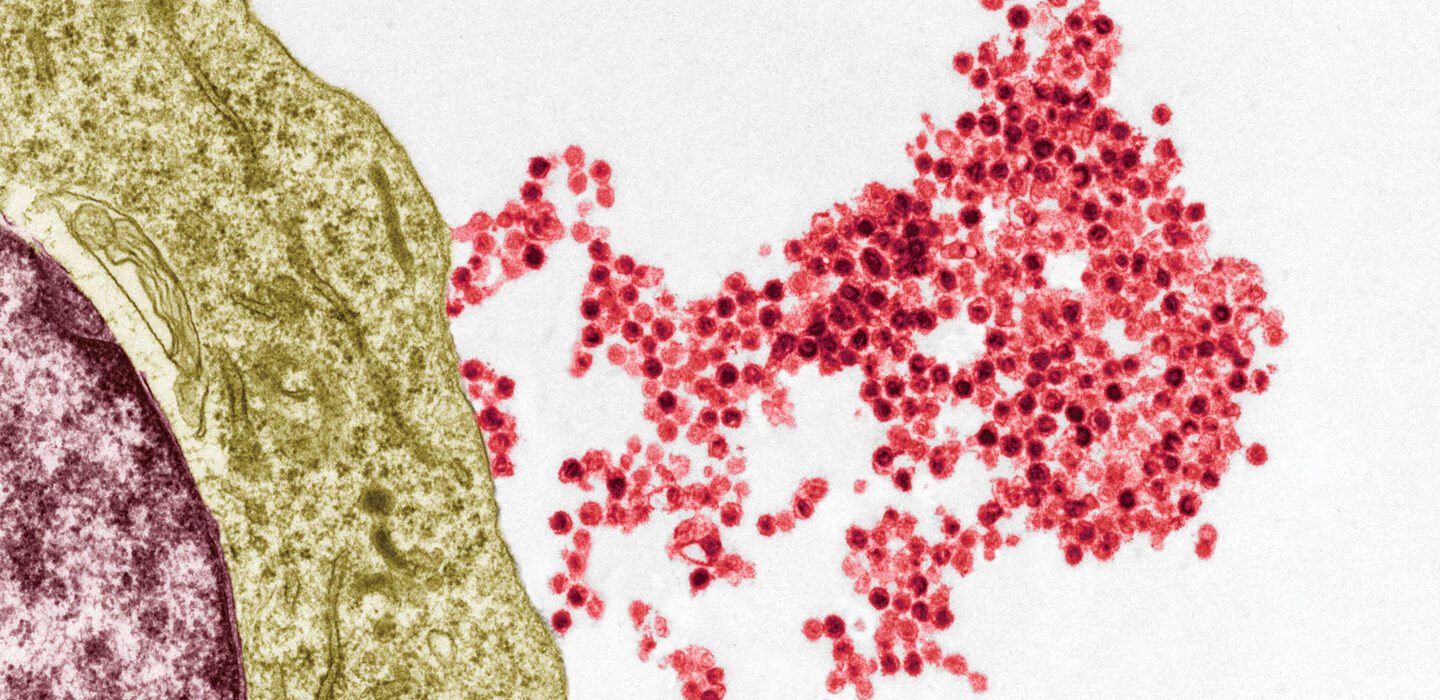

In the body, Epstein-Barr virus slips into the epithelial cells that line the surface of the throat, allowing the virus to spread to other people via saliva — hence mono’s nickname, “the kissing disease.” The virus also infects a type of immune cell called B cells, where it enters viral hibernation.

Epstein-Barr virus can cause problems long after the initial infection. People who had mono are more likely to develop cancers such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma than people who didn’t. And they are more likely to be diagnosed with MS. A teenage case of mono doesn’t mean long-term problems are inevitable. But avoiding mono-related fatigue doesn’t guarantee an escape from risk either. Agosto, for instance, doesn’t recall ever having mono.