Tokyo, 26 December, /AJMEDIA/

As tiny glass frogs fall asleep for the day, they take almost 90 percent of their red blood cells out of circulation.

The colorful cells cram into hideaway pockets inside the frog liver, which disguises the cells behind a mirrorlike surface, a new study finds. Biologists have known that glass frogs have translucent skin, but temporarily hiding bold red blood brings a new twist to vertebrate camouflage (SN: 6/23/17).

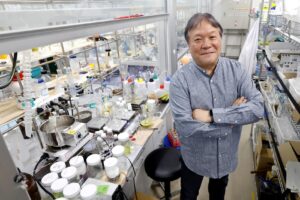

“The heart stopped pumping red, which is the normal color of blood, and only pumped a bluish liquid,” says evolutionary biochemist Carlos Taboada of Duke University, one of the discoverers of the hidden blood.

What may be even more amazing to humans — prone to circulatory sludge and clogs — is that the frogs hold almost all their red blood cells packed together for hours with no blood clots, says co-discoverer Jesse Delia, now at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Wake the frog up, and cells just unpack themselves and get circulating again.

Hiding those red blood cells can double or triple the transparency of glass frogs, Taboada, Delia and colleagues report in the Dec. 23 Science. That greenish transparency can matter a lot for the snack-sized frogs, which spend the day hiding like little shadows on the undersides of the leaves high in the forest canopy.

What got Delia wondering about transparency was a photo emergency. He had studied glass frog behavior, but had never even seen them asleep. “They go to bed, I go to bed — that was my life for years,” he says. When he needed some charismatic portraits, however, he put some frogs in lab dishes and at last saw how the animals sleep the day away.

“It was really obvious that I couldn’t see any red blood in the circulatory system,” Delia says. “I shot a video of it — it was crazy.”

As he pitched his project to a Duke University lab for support, he was stunned to discover that another young researcher was pitching the same lab to study transparency in glass frogs. “I was like, oh, man,” Delia says. But the leader of the biological optics lab at Duke, Sönke Johnsen, told Delia and his rival, Taboada, that they had different skill sets and should tackle the problem together. “I think we were hardheaded at first,” Delia says. “Now I consider him as close as family.”