Tokyo, 29 April, /AJMEDIA/

Humans eat more than 30,000 species of plants and animals. But for the most part we don’t know much about what is in them. Researchers have thoroughly analyzed the molecular components of only a few hundred of the most common foods, leaving a vast gap in our knowledge of nutrition.

This week, food scientists and activists met here to launch a new database that aims to close that gap. The database, part of a project called the Periodic Table of Food Initiative (PTFI), spearheaded by the Rockefeller Foundation, aims to document the vast array of biomolecules found in food, with a long-term goal of aiding efforts to improve agriculture, nutrition, and health.

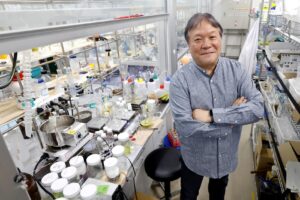

“Our planet has this incredible edible biodiversity,” Selena Ahmed, an ethnobotanist at Montana State University and global director of PTFI at the American Heart Association (AHA), said at the database’s unveiling on 24 April. But most compounds in the plants, meat, fish, and dairy products that we eat have never even been named and represent the “dark matter of food,” said Chi-Ming Chien, co-founder of Verso Biosciences, which is aiding in the effort.

To dramatize the surprising molecular diversity in foods, Chien showed the results for one sample of quinoa. It contained 6000 distinct proteins, mostly designated by crypticstrings of numbers and letters. “This platform allows us to analyze the complexity of foods in a way that was simply not possible before,” he said.

The initiative—which in addition to AHA has partnered with universities and nonprofits—has compiled information on about 500 foods, with 1600 more in the pipeline. Unlike previous food composition tables—which focused on macronutrients such as fats, proteins, and carbohydrates—the new database includes information on a much wider group of compounds, including micronutrients and specialized metabolites, some of which may help prevent disease. To collect those data, PTFI has partnered with more than 20 research laboratories globally. To date, the Rockefeller Foundation and other funders have spent more than $30 million on the multiyear effort.

“With a rapidly growing [world] population … growing enough food was clearly an urgent priority,” said Bruce German, director of the Foods for Health Institute and chair of PTFI’s advisory board. But the consolidation of agriculture into fewer high-yielding crops, he says, has in some parts of the world impoverished diets and contributed to mortality. To help correct this, the initiative is focusing attention on lesser known indigenous food plants, which can be better suited to local growing conditions and more nutritious than some popular commercial crops.

Eventually, organizers hope the database will enable researchers to compare the nutritional value of foods produced in different places and by different techniques, including large-scale monocultures and organic agriculture. It will also track how climate change is shaping the molecular content of plants. Such information could help “feed people in a way that is regenerative to the planet, equitable, and nutritious,” says John de la Parra, director of the Global Food Portfolio at the Rockefeller Foundation.

In addition to building the food components database, PTFI is involved in several research projects. One led by ethnobotanist Alex McAlvay of the New York Botanical Garden is examining practices in the Wollo Highlands of Ethiopia. There, farmers have historically sown mixtures of different kinds of seeds in the same fields, a practice that helps protect against crop failure during droughts and insect infestations. The strategy could also have health benefits “When various crops are planted together, harvested together, and consumed together, they appear to be complementary nutritionally leading to a better diet,” McAlvay says, adding that he hopes such research will help revitalize traditional agriculture and improve commercial farming.

The initiative could “bring nutrition [research] into the 21st century,” says Jess Fanzo, a food system expert at Columbia University who is not involved in project. It will not only help train scientists around the world, she notes, but also encourage the adoption of “uniform global standards for food analysis,” which will make it possible to compare results generated in different laboratories.

Access to the data interface is open to all, but is built for use by researchers. Organizers also plan to eventually open a gated database to the food industry, Ahmed says, and also make customized data interfaces for farmers and consumers.