Tokyo, 28 September, /AJMEDIA/

The coral reef, once bustling with more than 5,000 long-spined sea urchins, became a ghost town in a matter of days. White skeletons with dangling spines dotted the reef near the Dutch Caribbean island of Saba, the water cloudy from the disintegrating corpses. In just a week last April, half of the urchins, Diadema antillarum, in a section of reef called “Diadema City” had died. In June, only 100 remained.

The mysterious die-off started sweeping across the Caribbean in February. It’s eerily similar to a mass mortality event in 1983 that wiped out as much as 99 percent of the Caribbean Diadema population — a huge blow to not only the urchins, which have not fully recovered four decades later, but also the reefs. Without urchins grazing, algae can overwhelm a reef, damaging adult coral and leaving nowhere for new coral to settle.

Before the die-off, Saba’s coral cover — the part of a reef that consists of live hard coral rather than sponges, algae or other organisms — hovered around 50 percent. Today, that number is down to 3 percent.

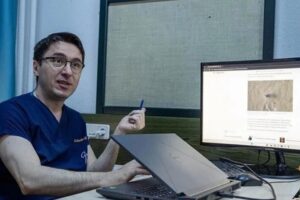

“It’s just downhill, downhill, downhill,” says Alwin Hylkema, a marine ecologist at Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences and Wageningen University in the Netherlands who is based in Saba (pronounced “say-bah”).

I learned about Saba’s sea urchin problem only shortly after I learned that the island existed. Saba is a blip in the Caribbean; at 13 square kilometers, it’s about a quarter the size of Manhattan, with the towering Mount Scenery volcano at its center. Its reefs attract scuba divers, but a lack of beaches shields it from regular Caribbean tourist traffic — hence its nickname, “the unspoiled queen.” What the island lacks in size and sand it makes up for with its great variety of species, its biodiversity. Steep cliffs support several microclimates. In just a few hours, a visitor can hike from volcanic rock to grassy field to misty cloud forest.

This diversity makes Saba the perfect spot for Sea & Learn, an annual educational program that brings scientists from around the world to the island. Former dive shop owner Lynn Costenaro launched the program in 2003 to encourage more divers to visit Saba during the off-season. But the event has grown to play an important role in educating the island’s 2,000 residents about their home’s unique wildlife and ecosystems.

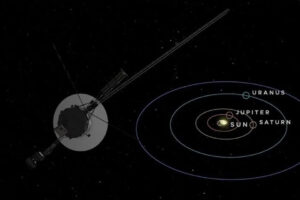

Throughout October, the scientists present their research on everything from biology and geology to astronomy at restaurants and in plazas. Several researchers also host public research trips underwater and on shore, so attendees can see the lobsters, or rock formations or stars for themselves.