Tokyo, 1 January, /AJMEDIA/

More liquid magma lurks beneath the Yellowstone supervolcano than scientists once thought. But don’t panic: That amount of magma, researchers say, is still nowhere near enough to portend an eruption any time soon.

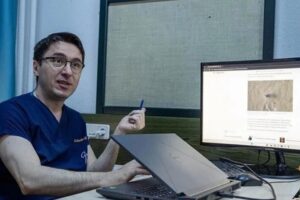

That reassurance comes courtesy of new state-of-the-art seismic images that give the sharpest picture yet of what lies beneath Yellowstone.

“It’s like getting a better lens for your camera. Things are coming into more focus,” says Michael Poland, a geophysicist who was not involved in the research. “We’re even less worried about an eruption now — and I wasn’t worried before,” adds Poland, who is the scientist-in-charge at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Yellowstone Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Wash.

The volcano beneath Yellowstone National Park has garnered interest — and worry — because it has had some of the most explosive, dramatic eruptions in the geologic record, he says. In the last 2.1 million years alone, Yellowstone has had three catastrophic eruptions, generating continent-wide ashfalls and disrupting the global climate.

The most recent of those catastrophic outbursts was about 631,000 years ago, forming a crater about 70 kilometers across (SN: 1/2/18).

Yellowstone’s subterranean magma chambers mostly contain hardened, cooled crystals that are mixed in with some amount of molten material. How much magma there is relative to crystals can determine how ready a volcano is to erupt. The average amount of liquid magma in the volcano’s underbelly is between 16 and 20 percent, Ross Maguire, a geophysicist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and colleagues report in the Dec. 2 Science.

The “critical melt fraction” at which the volcano might be prepared to erupt is more like between 35 and 50 percent, the team notes.

Previously, researchers had estimated Yellowstone’s melt fraction as between 5 and 15 percent. The new estimates don’t represent an actual change — they’re based on a reanalysis of existing seismic data that required far more computational power than was possible in the past.

“We’re not absolutely pushing the limit in terms of what we can do,” Maguire says, “but we’re getting kind of close.”